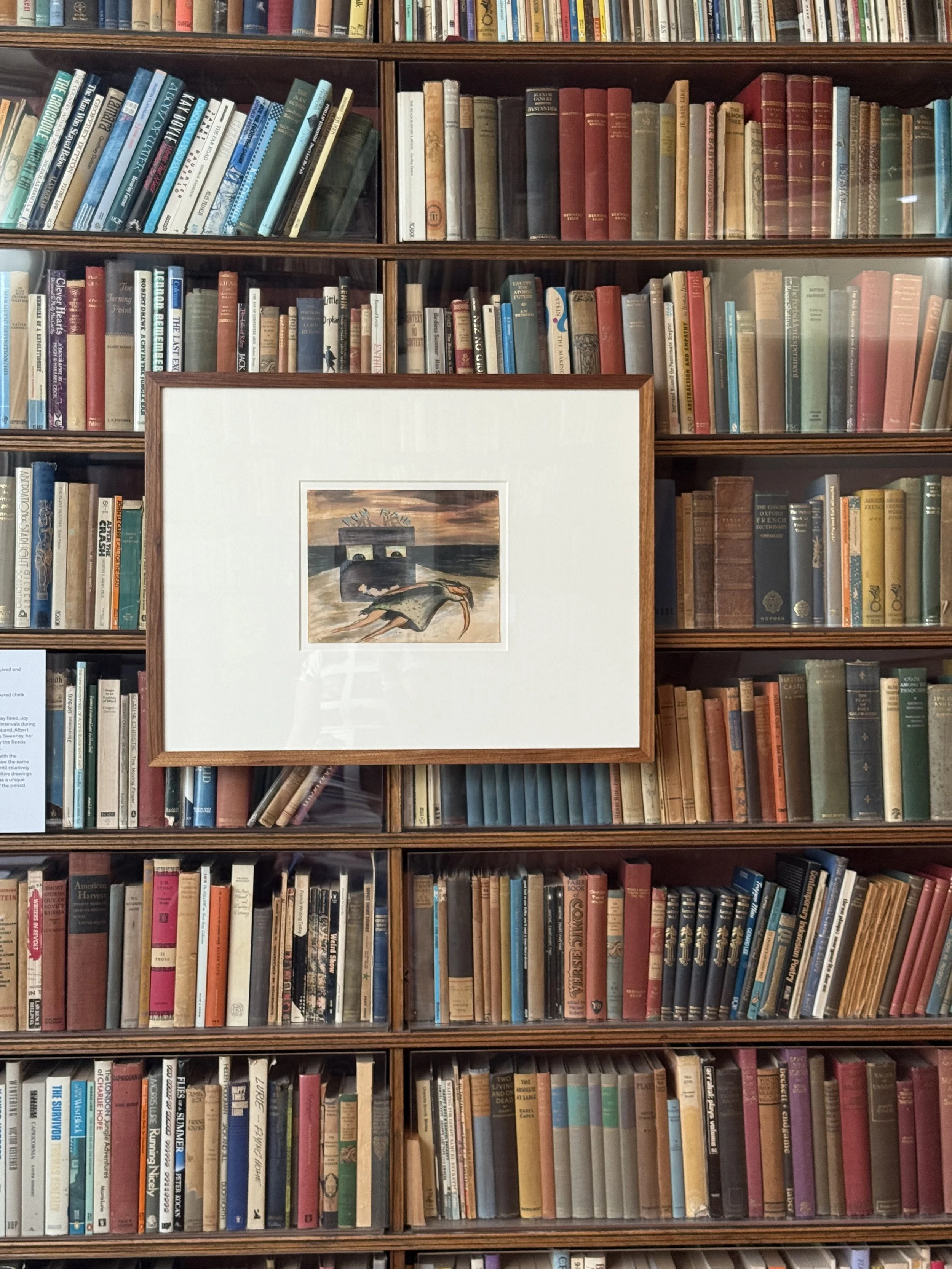

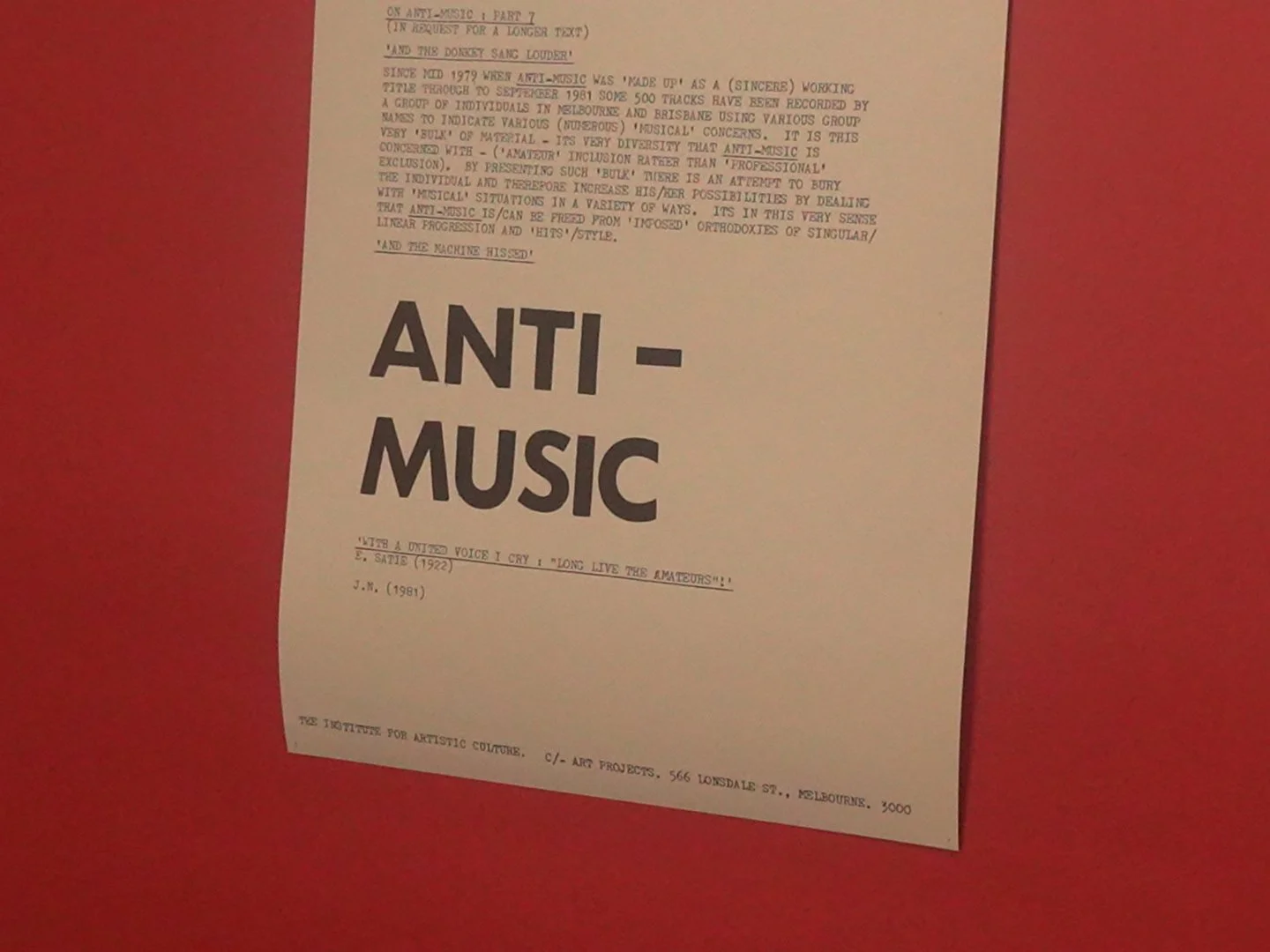

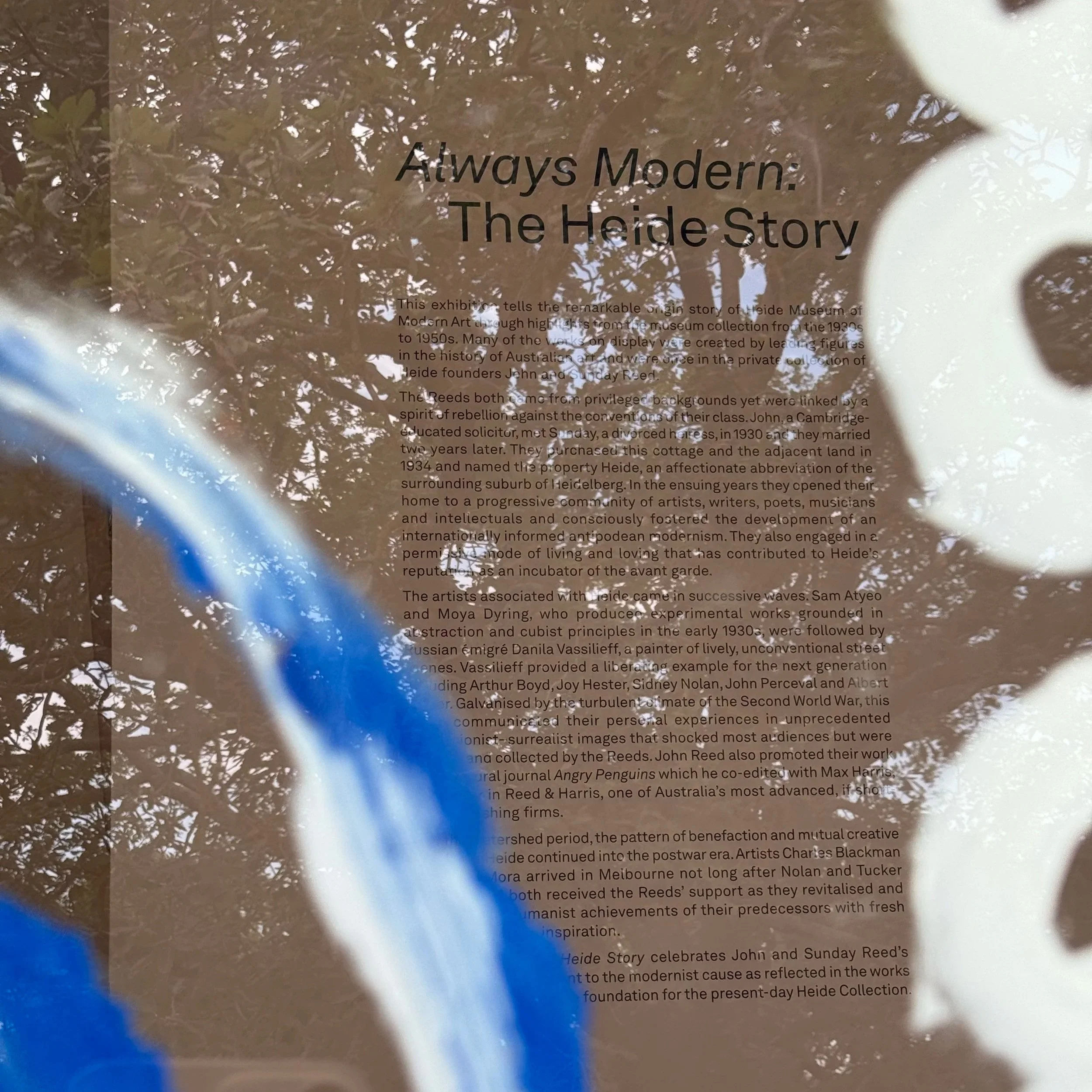

In the late 1930s, on a stretch of farmland beside the Yarra River in Bulleen, John and Sunday Reed created something quietly revolutionary. Their home—later known as Heide I—became a refuge for artists who didn’t fit neatly into conservative Australian society. Painters, writers, thinkers came not just to visit, but to stay, argue, love, create. Art wasn’t separated from life; it was lived daily, at the kitchen table, in the garden, in long conversations that stretched late into the night.

This community would later be called the Heide Circle, and it shaped the direction of Australian modernism. Artists like Sidney Nolan, Albert Tucker, Joy Hester, Arthur Boyd, and John Perceval found at Heide the freedom to experiment, to fail, and to be unapologetically modern. Nolan famously painted parts of his Ned Kelly series here—images that would become icons of Australian art history.

But Heide was never static.

In the 1960s, the Reeds built Heide II, a stark, modernist limestone house inspired by European architecture—designed as a “gallery to live in.” It was bold, intellectual, and uncompromising, mirroring the Reeds’ belief that art should challenge comfort rather than decorate it.

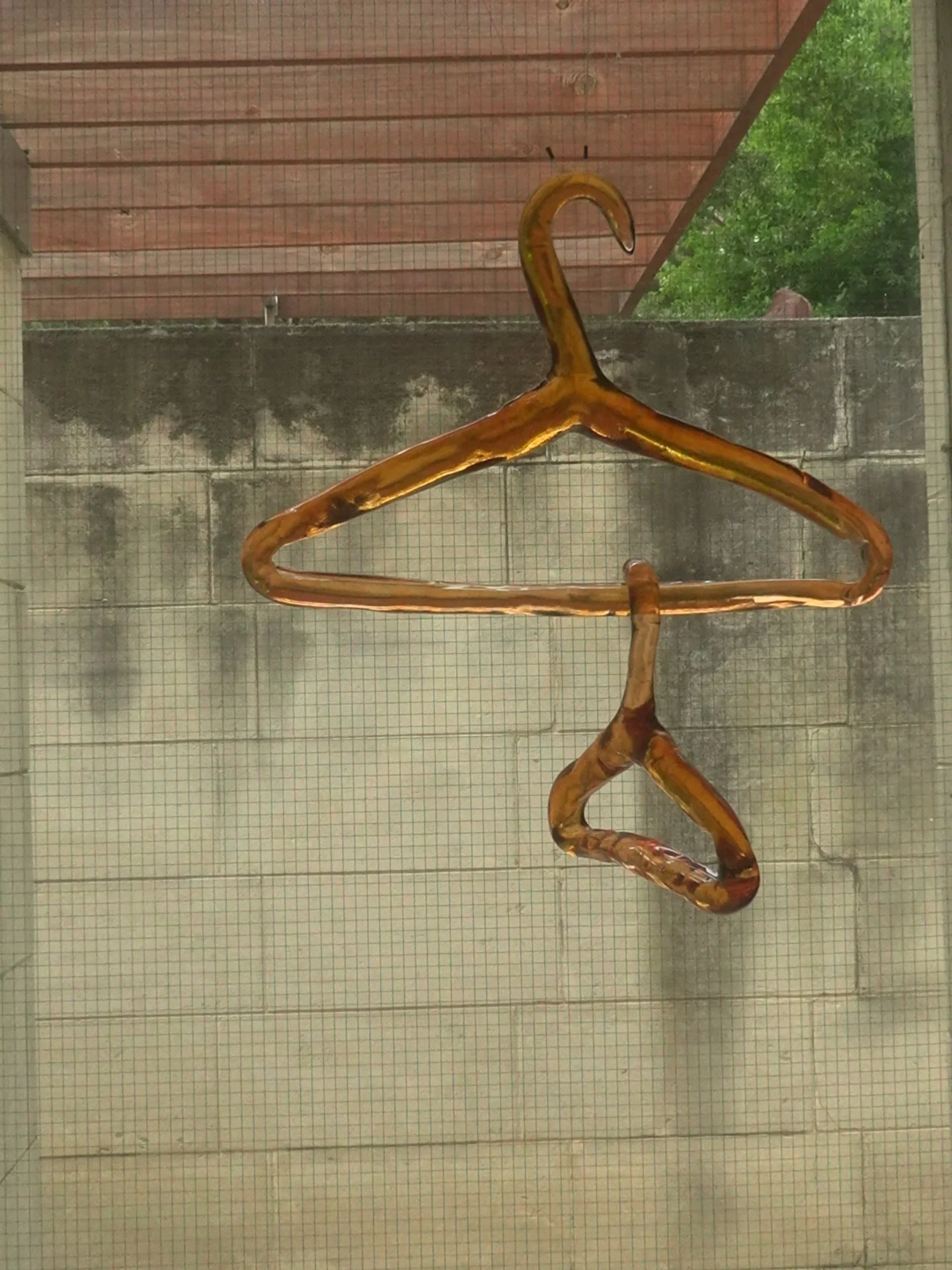

Eventually, what had begun as a private act of patronage transformed into a public legacy. In 1980, Heide opened as a museum, evolving into what we now know as the Heide Museum of Modern Art as a place where contemporary art, architecture, and landscape exist in constant dialogue. The sculpture park, the gardens, the shifting exhibitions all echo the original ethos: art is not confined to walls; it’s part of how we move through the world.

At its core, Heide’s story is about risk, generosity, and belief—belief in artists before they were celebrated, belief in ideas before they were accepted, and belief that culture grows best when given space to breathe.